- Air Homepage

- Air Quality Testing

- Output So2

- Flare Stack in BC

Clean air, smarts, and real decisions shape the future of your Flare Stack in BC

Environmental science and energy development are more interconnected - and more interesting - than most students realize. This article walks young readers through a blend of topics that shape real careers: how flare and venting rules protect communities and ecosystems; how dispersion modelling plays a crucial role in public safety in the Canadian province of British Columbia (BC); how companies navigate shifting project scopes and professional requirements affecting the development and usage of a flare stack in BC.

Get a glimpse into how regulations work on the ground, and how you might tackle the complicated scientific and operational problems affecting the flare. See the hidden gears that keep energy systems running safely, and the hidden gears inside the people who run them.

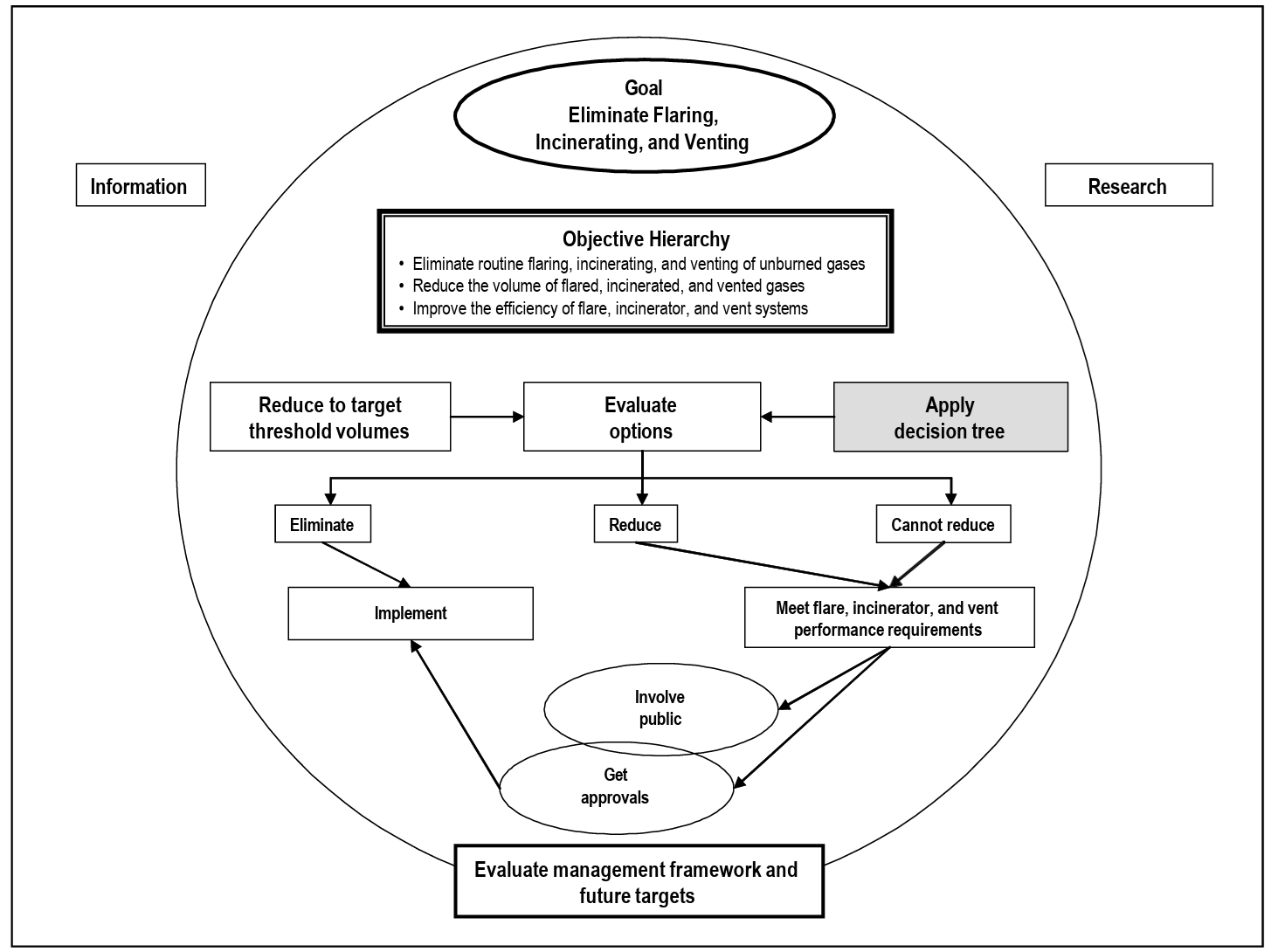

Framework for Managing Flares and Vents

Framework for Managing Flares and VentsClean air in BC: How smart decisions shape it - Energy is not just pipes, flames, and steel - it's a living system that breathes with every decision we make. If you've ever wondered how clean air, good science, and real-world judgement collide at a flare stack, here's your insider look.

Introduction comments and definitions

It's the BC Energy Regulator's mission to save gas. The main goal is to get the oil industry to stop burning (flaring) and venting the natural gas that comes out of the ground with oil, called "solution gas". Basically, they define conservation as catching that gas and using it for something else, like powering the facility itself, selling it, or re-using it. Saving gas might be either cheap enough (economic) or too expensive and thus impractical (uneconomic).

Venting isn't an option - The Regulator says venting isn't a good backup if you can't save the gas. If there's enough gas to keep a flame lit, burn it; otherwise conserve (save) it. Even when venting is the only option, you still have to follow special rules to do it safely.

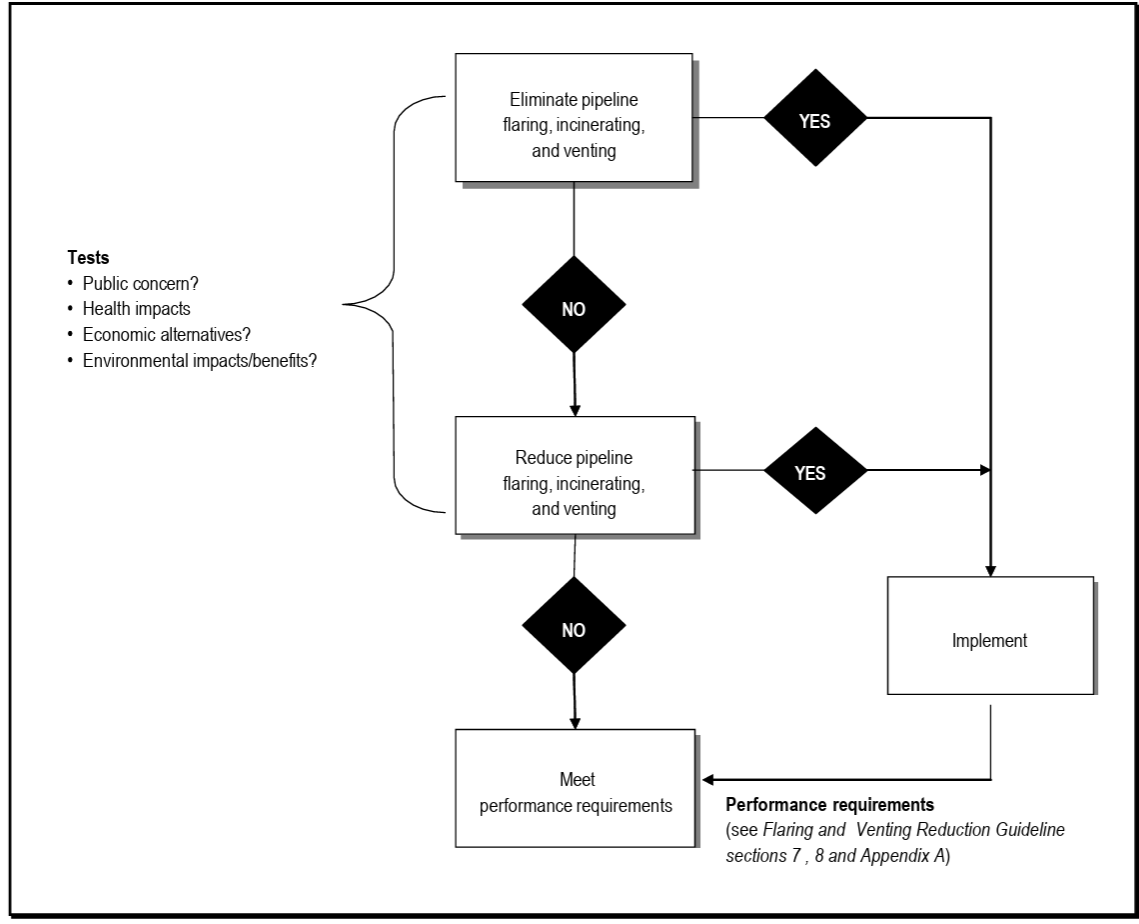

The Gas-Wasting Flowchart - Companies have to use a flowchart to figure out what to do with the gas. To help companies manage solution gas, the Regulator adopted a "Decision Tree" flowchart. It is a requirement for companies that plan to flare more than 900 cubic meters of gas per day to use this flowchart to show the regulator how they decided whether to use a Flare Stack in BC, a vent, or (ideally) conserve.

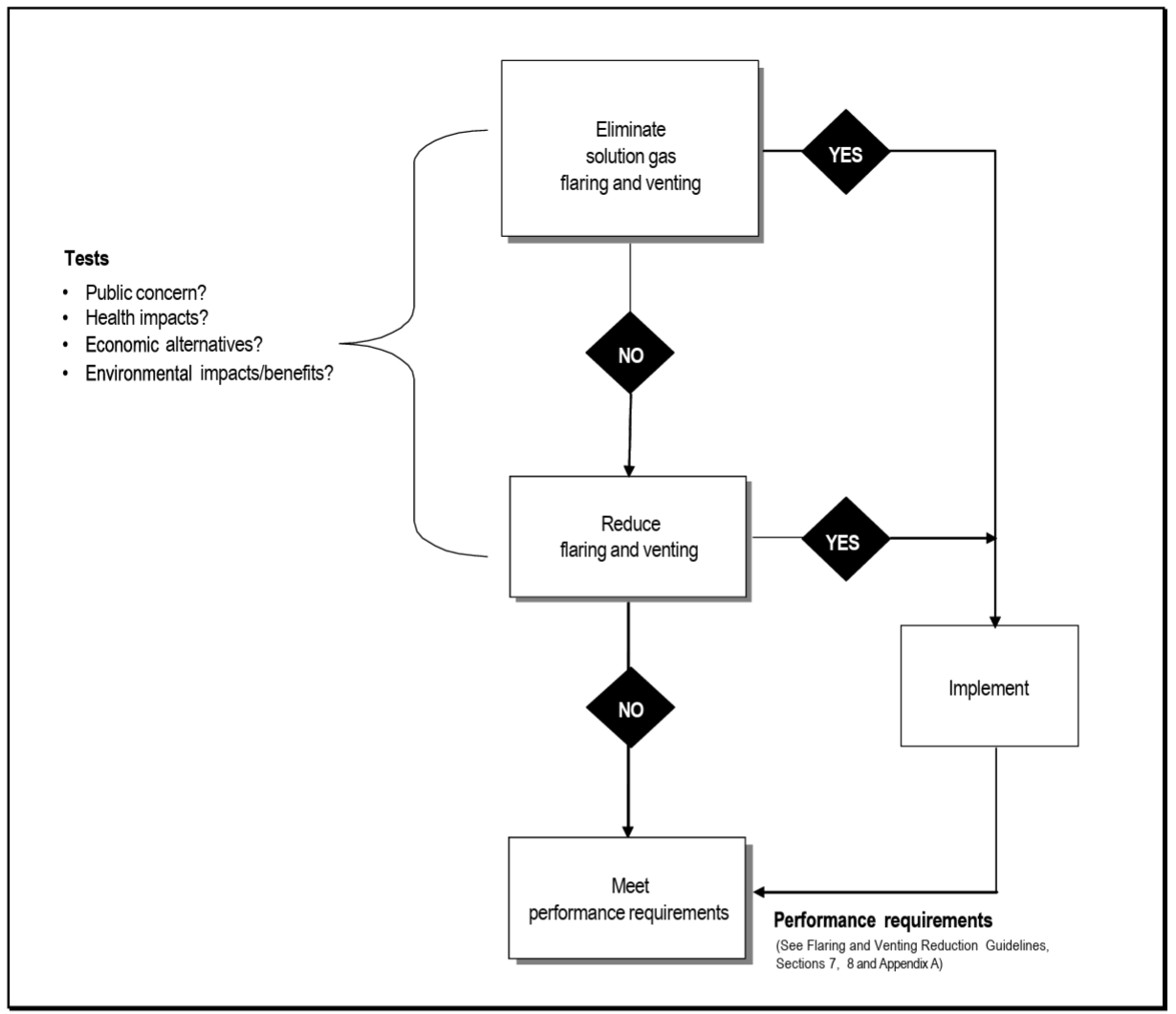

An easy way to make a decision about venting and flaring

An easy way to make a decision about venting and flaringNEW OIL FACILITIES: CONSERVATION - New oil sites shouldn't flare gas for too long—just long enough to test the well and size equipment. Anything over 72 hours needs special rules (anchor to chapter 2.3). The well should be shut down until conservation is ready if the gas is worth saving, that is if the net present value (NPV) is better than -$50,000. Consider using an incinerator if you can't conserve and the flare stack in BC would be visible from town.

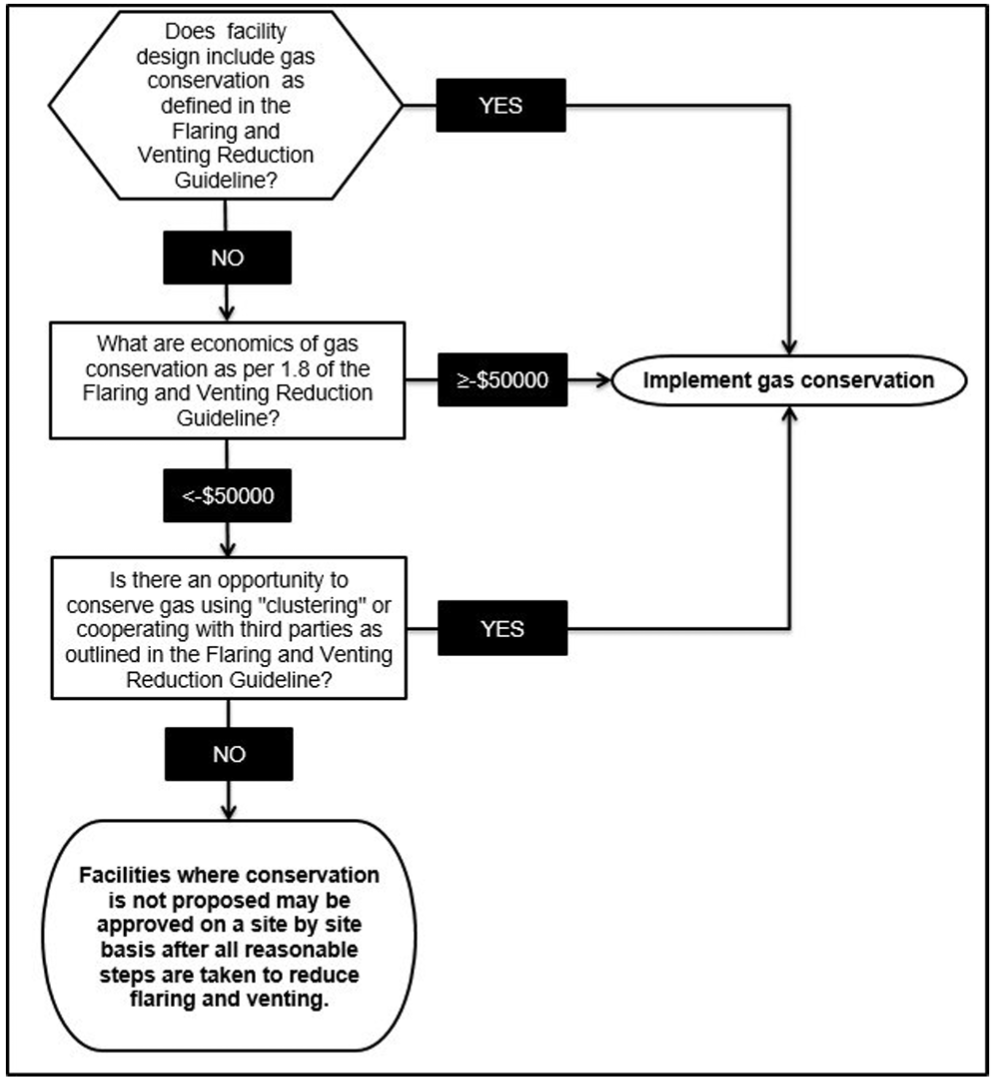

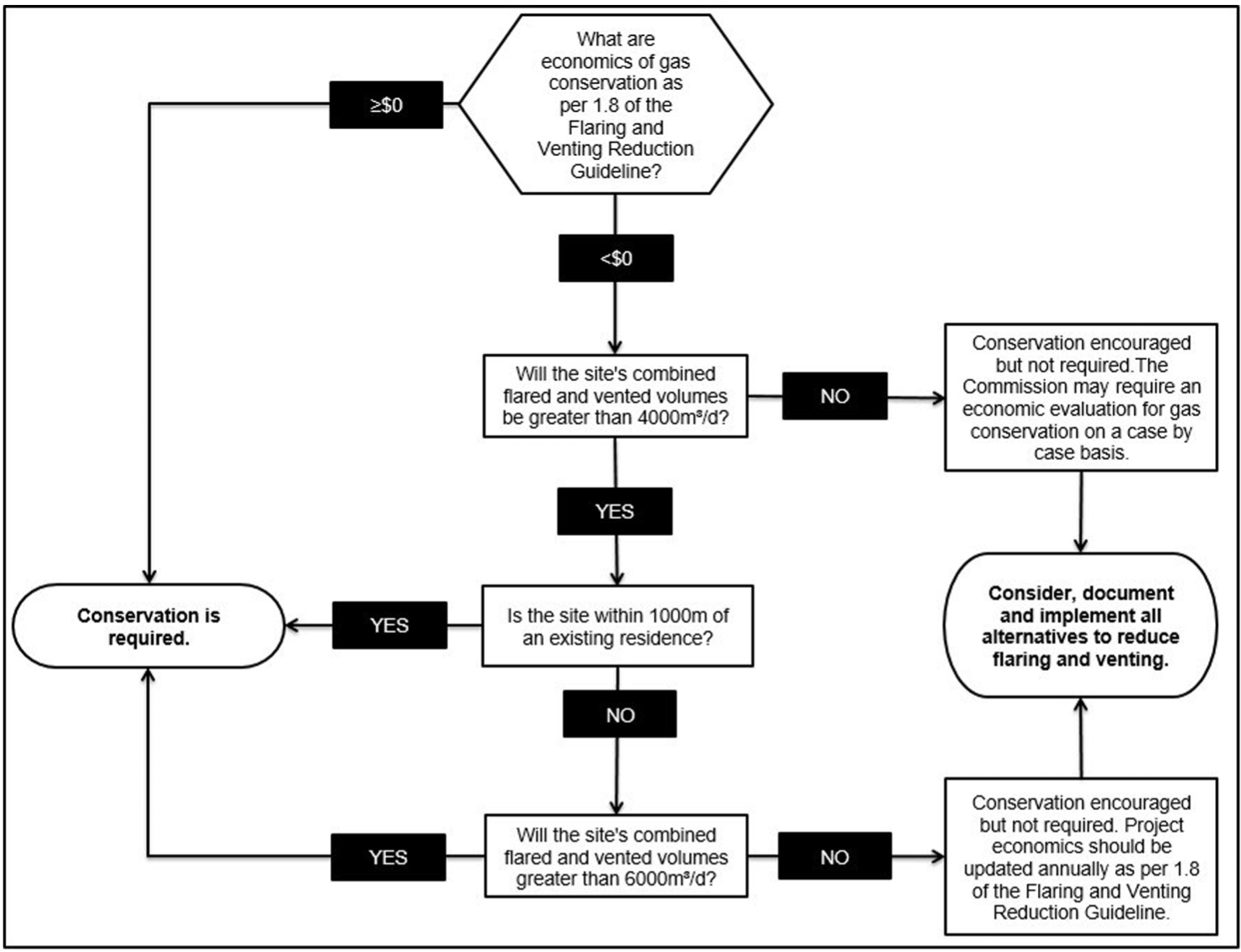

Decision Tree for Gas Conservation at New Oil Facilities

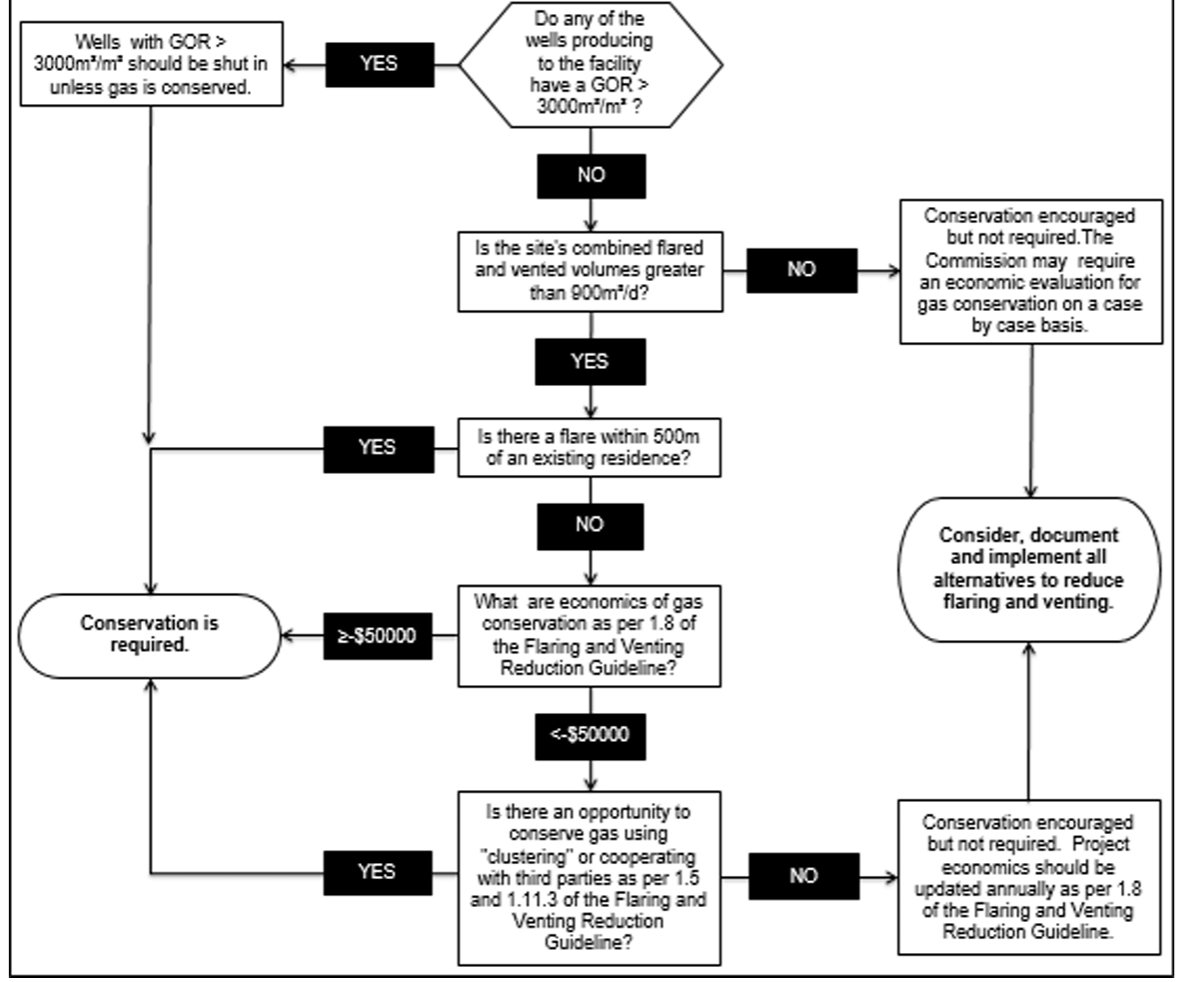

Decision Tree for Gas Conservation at New Oil FacilitiesEXISTING OIL FACILITIES: CONSERVATION - Existing sites have to conserve gas when they flare or vent a lot (over 900 m3/day), have a high gas-oil ratio (over 3000), or flare close to homes. Every year, they should recheck the economics and try to save 95% of the energy. Follow this decision tree. Note: GOR stands for gas-to-oil ratio.

Decision Tree for Existing Oil Facilities Regarding Gas Conservation

Decision Tree for Existing Oil Facilities Regarding Gas ConservationCLUSTERING - If lots of nearby wells are producing small amounts of gas, they can team up and send it all to one place. For big multi-well projects, operators within 3 km should share data and plan together.

GENERATION OF POWER - Gas can be used to make electricity instead of wasting it. It counts as conservation and can be smart.

NOTIFICATION & CONSULTATION - Companies must tell the public what's going on before they apply for flare wells. Companies (applicants) have to consult "rights holders" before applying for energy projects (e.g., oil/gas activities). It's about avoiding harming their interests and coordinating resource use. How to do it?

Engagement (for approvals and activities):

- Details about applicant, project location/description, maps, timelines, and how to respond (e.g., contact applicant, submit to regulator).

- Use approved service methods (like mail/email).

- There's a service period (delivery) and a response period (e.g., 30 days). Submit your app after, or sooner, with a non-objection letter/variance.

- Make a line list; include responses/replies.

- Changes/cancellations should be notified.

Specific details for water (Water Sustainability Act):

- Water licensees, applicants, riparian owners (land near water), and affected landowners should be notified.

- Regulator's name, map, project details, and 30-day objection period.

- Use tools like Water Licenses Query to find landowners.

- There are special rules for certain watersheds (like environmental flow requirements).

Responses and issues:

- Regulator lets rights holders submit written concerns anytime.

- Respond to the build resolution; track in line.

- Concerns unresolved: detail in app; regulator may approve, suggest more talks, or use dispute facilitation (e.g., mediation).

- When standard isn't practical, request alternate methods.

Focus on First Nations:

- Crown consultations for Treaty/Section 35 rights are handled by the regulator.

- Agreements, consultative areas; Treaty 8 has specific mitigation measures (e.g., wildlife plans, wetlands).

- Share plans early, log discussions, upload records.

Fair, informed decisions are made this way.

EVALUATION OF GAS CONSERVATION FROM AN ECONOMIC POINT OF VIEW - Every site that flares over 900 m3/day has to rerun the "Is it worth saving the gas?" math every year. Standard price forecasts, cost rules, and a simple test: if the NPV is better than -$50k, you must conserve. The costs have to be calculated realistically with no padding and done before taxes. The rules for power generation are a little different. You try again next year if the estimate is not in your favour.

REQUIREMENTS FOR ECONOMIC EVALUATION AUDITS - Companies must show all the math and data behind their economic calculations-costs, reserves, forecasts, analyses, and alternatives.

NON-ROUTINE FLARING & VENTING - A flare stack in BC has to be kept to a minimum when something breaks or a plant shuts down. Your affected plant might have to cut production by 50–75% depending on how long the outage lasts. Notify the regulator and your neighbors. Flaring wells with lots of H2S isn't allowed. The company needs to fix the problem if it keeps happening. Table 1.1 in the official BC document covers non-routine flaring and venting during solution gas conserving facility outages.

TURNAROUNDS (Planned shutdowns) - Companies need a plan to avoid major flaring events - like sending gas to another plant or timing maintenance across facilities.

SHUT-IN ALTERNATIVES - Operators can propose alternatives if shutting in wells isn't feasible, but they have to ask the regulator 30 days before the shutdown.

NOTIFICATIONS & APPROVALS FOR NON-CONSERVING FACILITIES - Flaring for emergencies doesn't need special approval, but an ongoing flare stack in BC does. However, it's always good to notify residents and the regulator.

REQUIREMENTS FOR SOLUTION GAS REPORTING - Gas flared, vented, or burned must be reported monthly in Petrinex (Canada's Petroleum Information Network, a collaborative online platform for governments, regulators, and the oil and gas industry to share volumetric, royalty, and regulatory data). Before reporting a new oil well, you need a battery code. Except for confidential projects, most production data is public. Your flare stack in BC might need a special request for flare data.

THIRD PARTY COOPERATION - The Regulator encourages sharing data and even handing over gas at no cost (unprocessed) if a third-party can save gas better than the operator. It's important that third parties are qualified and follow the rules.

An Overview of Well Flaring

Workers can burn leftover gas when testing or cleaning up a well, but they can't just let it vent into the air. Gas must burn if it can. There are strict rules for venting; it's the last resort.

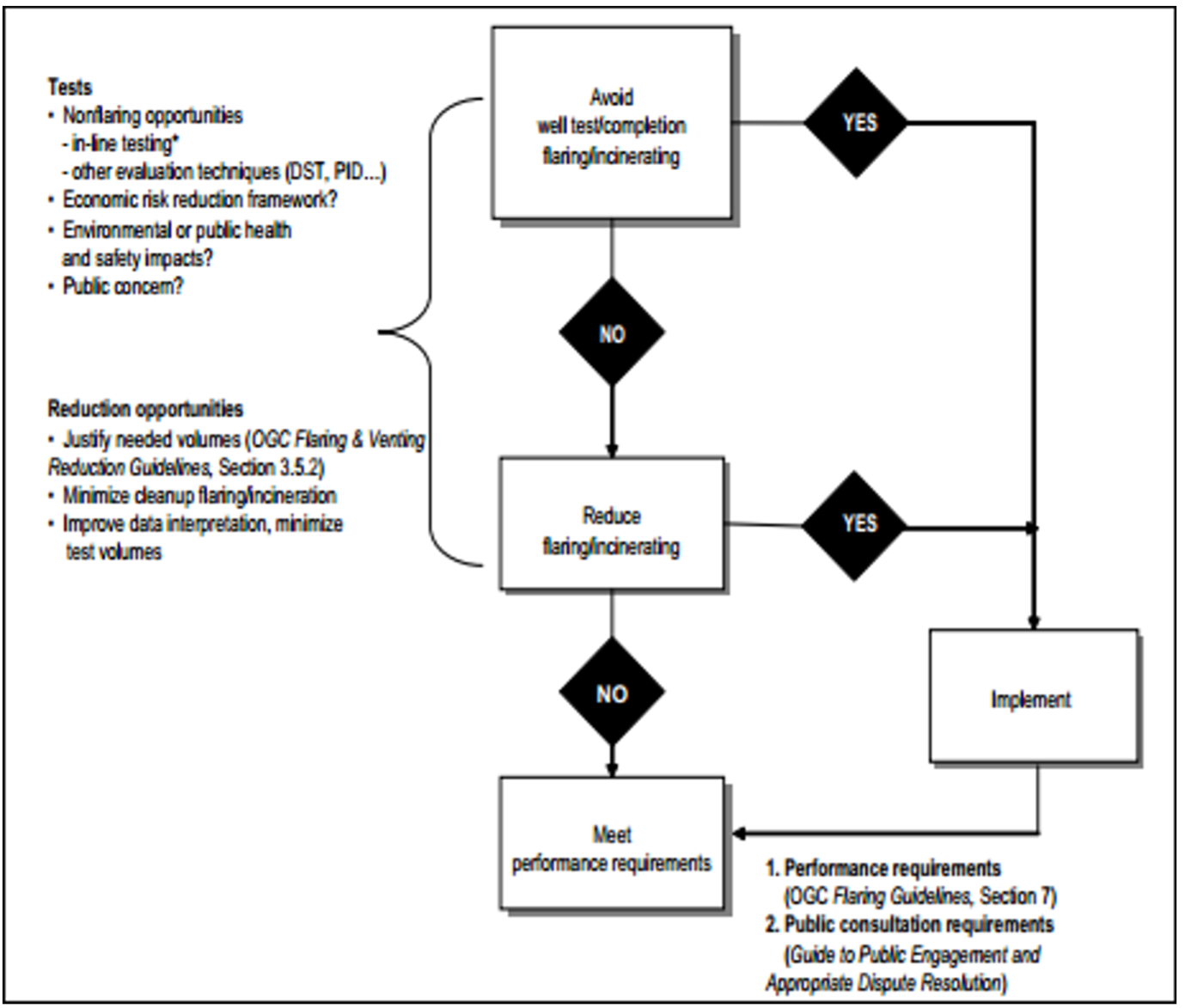

Decision Tree for Temporary Flaring

Companies should check every possible way to avoid flaring before burning anything - like hooking up to a pipeline. In a lot of places, you have to test a well through a pipeline (in-line testing). Alternatively, they can design the well test to keep emissions low while still getting the data they need.

Follow the BC well testing guide, which covers oil and gas well pressure surveys and well flow tests, including initial/annual requirements, quality standards, exemptions, submissions within 60 days, and disposal, DFIT (diagnostic fracture injection test), flaring, and delivery tests. See the diagram for making these decisions.

An adaptation of Alberta's CASA's temporary flare decision tree

An adaptation of Alberta's CASA's temporary flare decision treeReducing flare impact

Flaring near people should be kept to a minimum. It can mean reducing noise, flaring during the day, or using smokeless incinerators. If the public is worried, the regulator can even require incinerators.

Approvals for a temporary flare stack in BC

Flaring is allowed in some situations, such as drilling, emergencies and small maintenance jobs. They need explicit approval to test a well. Before they approve projects, regulators look at safety, pollution limits, sulfur emissions, and what nearby residents think.

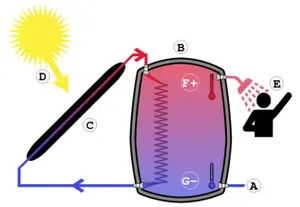

Evaluation of ambient air quality

Once the gas has a certain amount of hydrogen sulphide (H2S), companies have to use dispersion modelling to predict how the pollution will spread. Sometimes they just keep the models on file; with higher H2S, they have to send them to the regulator. Depending on the model results, the Flare Stack in BC regulator may set extra conditions such as stack height limits or ambient monitoring.

Flaring rules for specific sites

Equipment needs to be designed properly and run safely. Gas companies have to test the gas to see how sour it is (how much H2S it has) and if it's too sour, they have to stop. All flared volumes must be counted, and sour vapours need to be trapped.

Testing in-line and temporary pipelines

Companies can set up temporary compressors or surface pipelines to avoid wasting gas - but they have to get permission.

Notifications

Companies have to tell the regulator and people nearby before flaring. This includes where it's happening, how long, how much gas, and what's in it.

Flared volumes reported

All gas burned or vented must be reported to Canada's oil and gas reporting systems (eSubmission and Petrinex). Log every amount of recovered fluid and gas.

Flare Stack in BC and Gas Plant Venting

Introduction & Decision Tree

Even small, regular flares need to be stopped or reduced at gas plants and compressor stations. Also, they have to listen to residents' concerns.

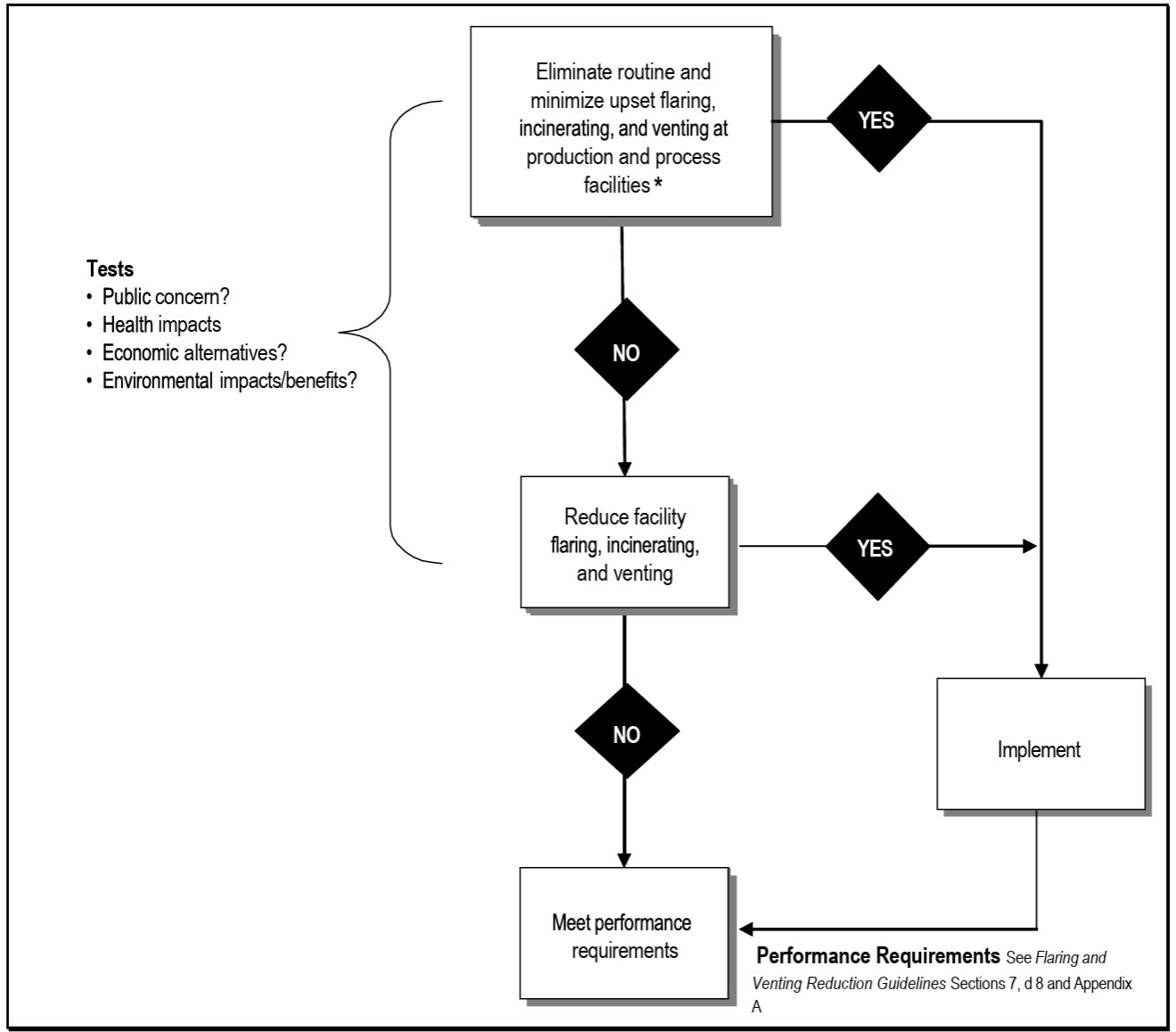

Flowchart for flaring and venting in facilities

Flowchart for flaring and venting in facilitiesRequirements for conservation

If saving the gas makes sense, or if the flaring is big and near homes, companies should conserve it. The economics have to be rechecked every year at sites with a lot of flaring. In general, big sites have to conserve unless the regulator says otherwise. See this figure for an overview.

Choosing a conservation strategy for gas facilities

Choosing a conservation strategy for gas facilitiesMeasuring

It's important to measure flared gas accurately. A flare meter may be needed if reports don't seem to be reliable. New plants need one automatically.

Notifications & Approvals

Maintenance and emergency flaring doesn't need approval, but non-routine flaring does. Notify people nearby.

Reports

Gas flared, vented, or incinerated must be reported monthly. Incinerator gas still counts as flare gas.

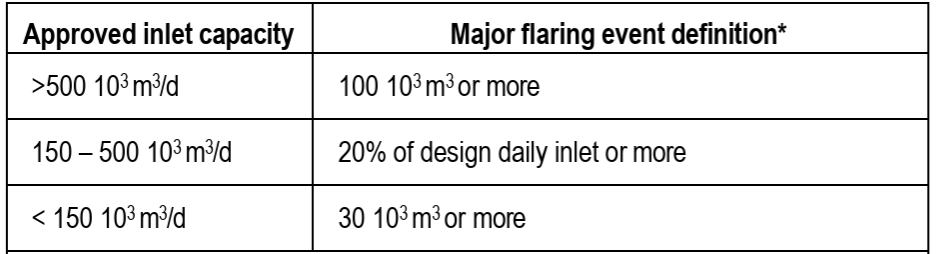

Non-Routine Flaring

The company must investigate, report, and change the approach to flaring events (reduce to less than six major events in six months) or face enforcement. Check this table to determine if your flareup is major...

Definition of an event of major flare-up

Definition of an event of major flare-upFlaring from a facility outage

If a facility goes down, companies need to process solution gas first, then choose the flare stack in BC that disperses emissions best.

Flaring and Venting in Pipelines

Each flare/vent event should be analyzed, alternatives considered, and unnecessary releases reduced. Additionally, they have to deal with public complaints and follow engineering codes.

Table of Decisions on Pipeline Flaring and Venting

Table of Decisions on Pipeline Flaring and VentingSpecial cases & Economics

There's no economic test for pipeline depressurization. When flaring would cause big disruptions for gas customers, venting is allowed.

Reporting & Notification

Pipelines have to notify residents and regulators when they use a flare stack in BC. Burned or vented gas has to be reported every month, and operators have to keep basic records.

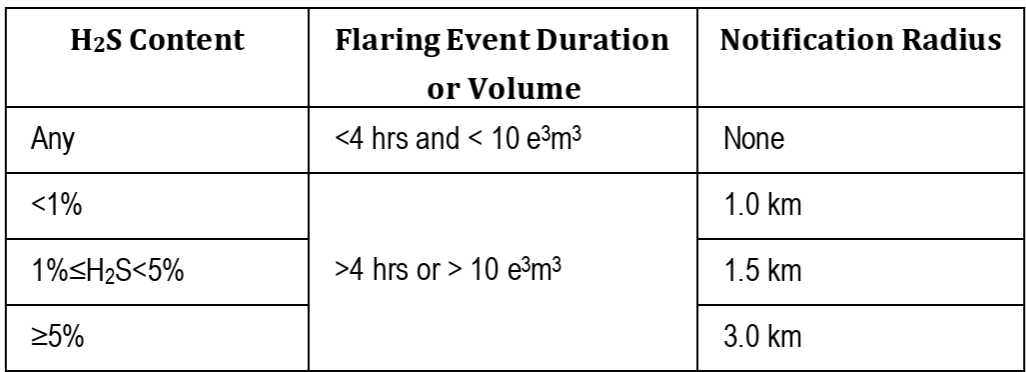

Notifications - When and Who needs to Know

If companies want to flare, they have to notify nearby residents and administrators - not ask for permission, just let them know. Radius depends on how sour the gas is and how long the flaring lasts. Provide basic info like location, duration, gas type, and contact info. Check this table:

British Columbia's Notification Requirements

British Columbia's Notification RequirementsNotification to regulators

The regulator must also be notified at least 24 hours in advance (or within 24 hours if it's an emergency).

Flares & Incinerators - Performance Requirements

Professional engineers should design and oversee any flare stack in BC. It's important to have written procedures and follow them. Companies have to show the flare setup works before using it if it's new or unproven.

What to expect

Flares can't create off-site odours, break air quality standards, or harm people or plants. In that case, the company has to fix it - even if it means replacing equipment.

Smoke rules

Black smoke is almost never allowed - only for 5 minutes every 2 hours. Smoke must be checked using official methods and records must be kept.

Flame Stability & Heating Value

Clean burning requires enough energy in the gas going to the flare (heating value). Companies have to add fuel gas if it's too weak or as specified by other applicable laws. To avoid flameouts or smoky burns, equipment must be sized correctly.

Combustors in enclosures

Any flare stack in BC with a hidden flame. There has to be no visible flame, cool outside surfaces, safe exhaust temperatures, and flame-arresting air intakes.

Flaring procedures for sour and acid gases

It's a good idea to have automatic shutdowns, trained staff, and documentation of dispersion evaluations at facilities that handle sour gas.

Requirements for spacing

Keep flares away from wells, tanks, and work areas so everyone is safe - usually at least 50 meters away.

Design for your Flare Stack in BC

Flares and incinerators need to be built safely: super hot flames, strong towers, and enough space to keep people, wildlife, and buildings from getting burned. Gas burners need to burn well (98% efficiency), stay away from buildings, and avoid scorching the ground. If it's safe, companies can adjust distances.

Using Pits for flaring

The old-school flare pits (burning gas in shallow dugouts) are being phased out. If you still have one, keep liquids out, stay under air-quality limits, avoid flaring gassy, smelly gas, and restrict access so nobody wanders into a zone that can cook a marshmallow.

The spark

Flares and incinerators must stay lit — no ghostly plumes of raw gas. There are automatic ignition systems, flame monitors, and alarms depending on how much H2S is in the gas. Regulators can force upgrades if they keep blowing out or causing odours. When gas shows up rarely and safely, manual lighting is allowed.

Separation of liquids

The gas often carries tiny droplets of liquid, which can make the flare stack in BC burn dirtier and stinkier. To catch the liquids before burning the gas, facilities use knockout drums. Drums need alarms, liquid storage, and regular emptying. You don't need alarms if someone is standing there the whole time.

Controlling the backflash

Backflash is basically fire running backward in a pipe. The companies use flame arrestors, purge gas, and strict procedures to stop that. Check valves are not adequate for this purpose. These fire-stopping gadgets can only be skipped by small, temporary flares supervised by humans.

Maintenance on flares

Flares need love too. Keep them clean, inspected, and carbon-free so they don't accidentally spark wildfires.

Modelling dispersion

SO2 and H2S from burning sour gas must not choke nearby communities or ecosystems. Most smelly gas flares require modelling unless they're for a very short time. Even cleaner gas (less than 1% H2S) might need modeling.

Modelling Rules

Use an approved model, use real numbers (not wishful thinking), and show the results. If simple modeling says "uh oh," then a more detailed model with local weather data is needed. It has to meet Canadian air-quality standards, especially for SO2. You can compare results to BC's well test flaring guidelines or Alberta's AER Directive 060 risk-based standards until BC makes its own. Non-routine flares can have concentrations rarely predicted to exceed air quality limits, but actual ones can't ever. To make the plume rise higher, companies may need special plans, procedures, or extra fuel.

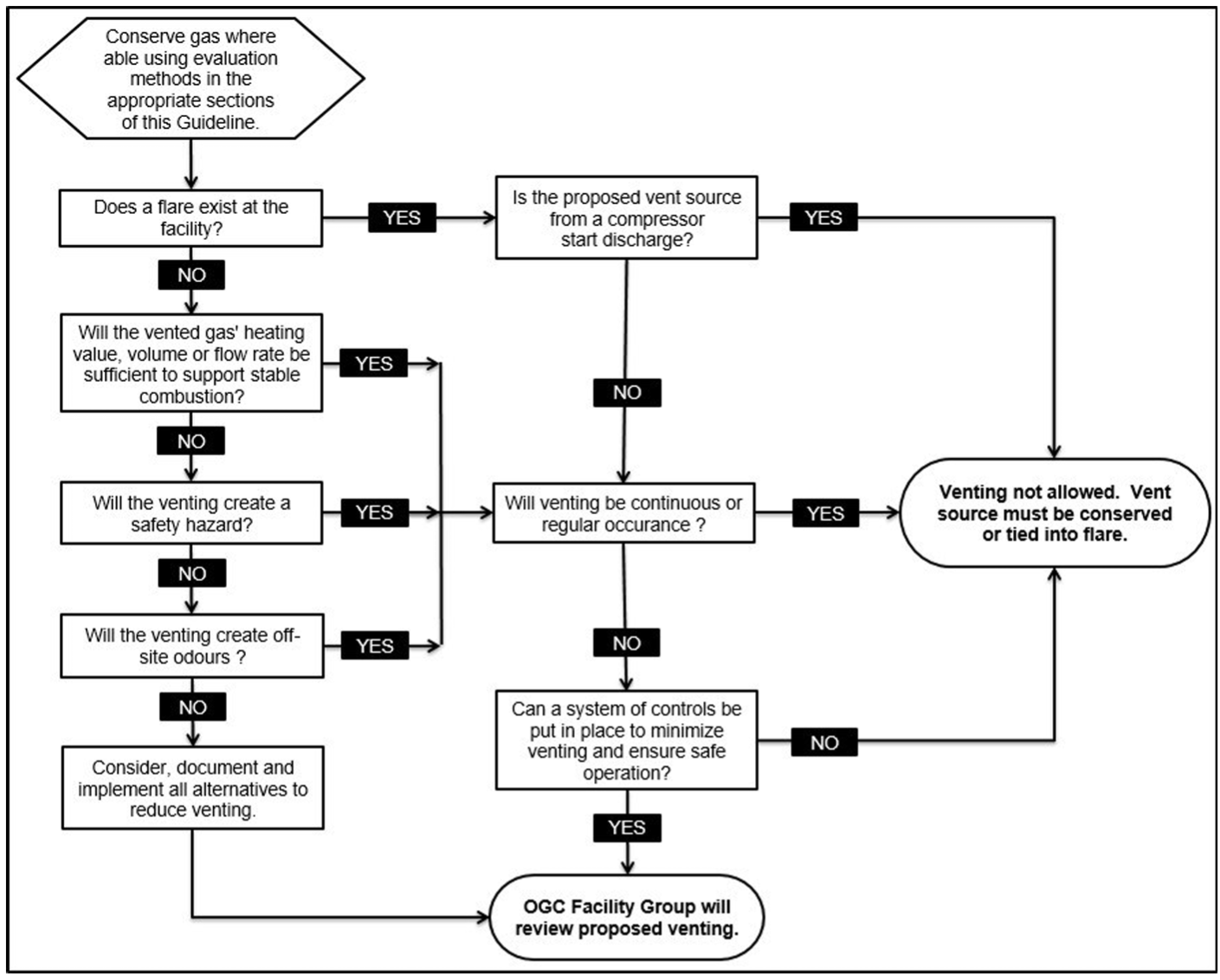

Fugitives & Venting

The least-favorite option is venting (releasing gas straight into the air). Gas should be burned if possible. There can't be any odours, no hazards, minimal amounts, and everything has to go through a decision tree.

British Columbia Venting Evaluation

British Columbia Venting EvaluationFacility venting rules

New and upgraded sites will have stricter rules: tanks, compressor seals, pneumatic devices, and pumps can't vent gas unless they meet very specific exceptions. These rules will apply to even older sites by 2035.

Exceptions to venting

You can only vent in an emergency, a tiny seasonal site, maintenance, or a one-off process upset. It has to be proven with engineering math and signed by a professional engineer if venting can't be avoided for safety, reliability, or extreme costs.

Gas venting with H2S

Please don't vent stinky, toxic gas. PSVs and blowdowns should go to a flare stack in BC. If not, the company must show they can handle it safely.

Benzene

Follow the benzene rules. It's a confirmed bad guy. The best way to control benzene emissions from glycol dehydrators, which are used to remove water from natural gas in oil/gas processing. BC Energy Regulator rules say we should keep emissions low to minimize human exposure.

Operational Requirements (Permit Holders):

- Emission limits are determined depending on when the dehydrator was installed or relocated and how far away it is from homes or public places such as schools:

- Until 1999: Up to 5 tonnes/year (t/yr) if >750m away; 3 tonnes/year if closer.

- From 1999-June 2007: 3 times a year.

- Max 1 t/yr after June 2007.

- Multiple units: Total emissions can't exceed the limit for the oldest dehydrator; upgrades may be needed.

- Units that are new or relocating must emit 1 t/yr; overall site limit still based on the oldest unit.

- During partial-year operation, prorate (adjust) emissions.

- Here's the required documentation:

- Make a DEOS (Dehydrator Engineering and Operations Sheet) to calculate emissions; post it on site and update it yearly.

- You have to submit your annual Benzene Inventory List online by March 31.

If you have questions, contact the regulator's Environmental Stewardship Group.

Venting non-combustible gases

Nitrogen and CO2 won't burn. If your mixtures don't smell bad, don't hurt air quality, and don't pose a safety risk, they can be vented. A regulator can require modelling if they suspect negative impacts.

Vents & fugitives in surface casings

You'll find those rules in the BC Oil and Gas Activity Operations Manual.

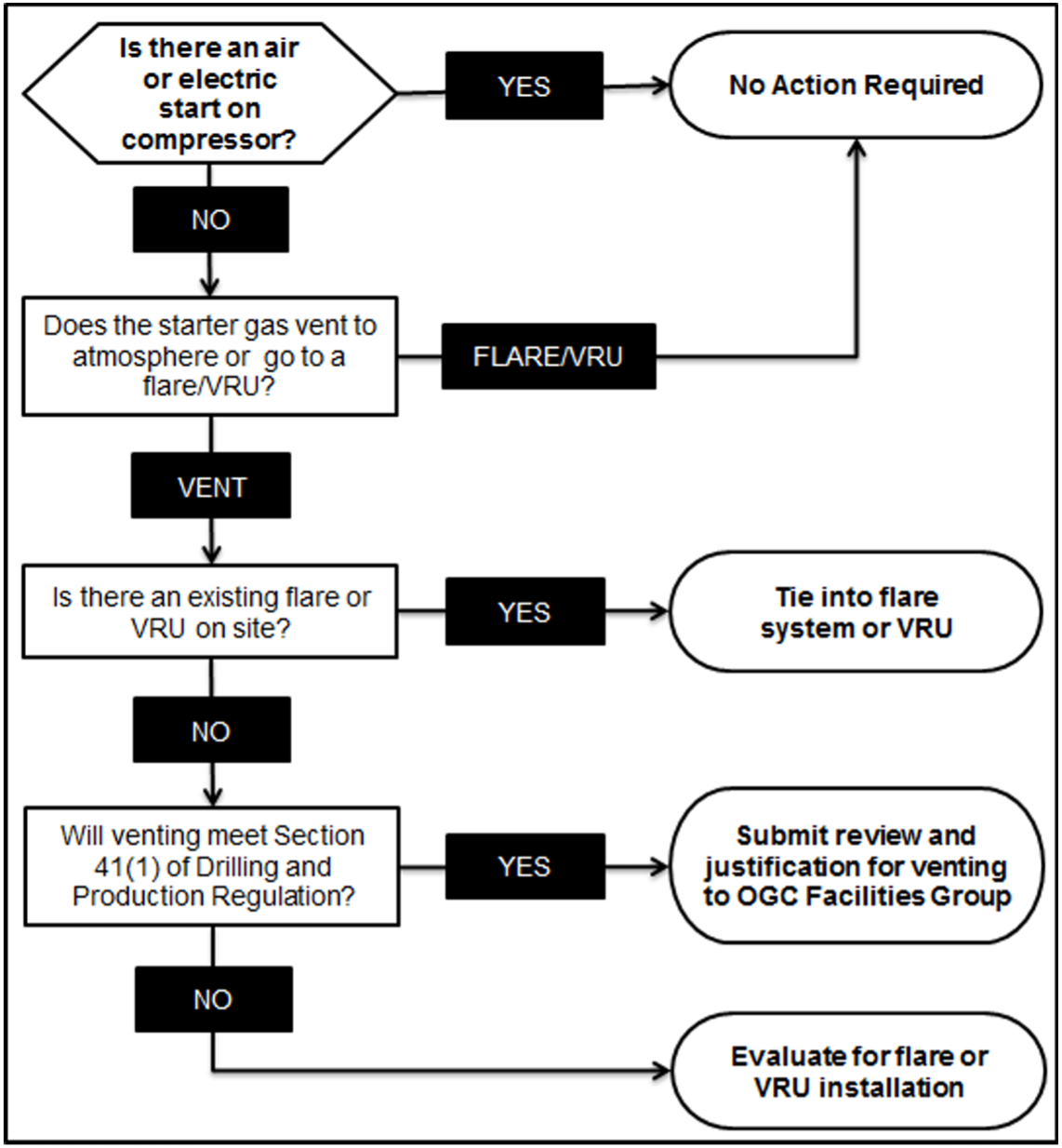

Start gas for compressors

Natural gas to start compressors? New sites have to flare it or conserve it. Old sites need a review to justify why they're still venting. The regulator can enforce changes if the justification is weak. Refer to this drawing:

Decision Tree for Compressor Start Gas Discharge in BC

Decision Tree for Compressor Start Gas Discharge in BCSulphur Recovery

Oil and gas sites can release sulphur into the air when they burn stinky sour gas. When a site burns enough sulphur-rich gas (more than two tonnes a day! ), the government says, "Time to clean it up!" and Sulphur recovery rules are written directly into each plant's air permit.

Incineration Evaluation

The decision to use a flare stack in BC (big open flame) or an incinerator (closed, cleaner burner) has a lot of factors to consider: local air quality, smoke, neighbours' feelings, how much flaring they'll do, how visible it is, and even noise. British Columbia basically says: choose the option that keeps the air clean.

Exit Temperatures & Residence Times

When the gas stays inside long enough and gets hot enough, incinerators work best. Here's the rule:

The gas should stay inside for at least half a second (unless it's super clean). Keep the exhaust at 600°C or higher. Especially for gas with lots of H2S, the system shall shut off if the temperature drops too low. Incinerators have to burn gas really well, with at least 99% efficiency or else they're treated like flares.

Measurement & Reporting

If you burn it, flare it, or vent it, you have to measure it and report it. Here's the Big picture:

- Even in an emergency, companies have to report almost all gas they burn or release.

- There are three types of gas: fuel gas (used for energy), flare gas (burned in a flare stack in BC or an incinerator), and vent gas (released unburned).

- Fugitive leaks don't count here; they're handled separately.

- Big sites should meter flare streams so they can report accurate numbers. The meters have to be accurate (kind of like school standards for calculators).

- If companies don't measure gas, they must estimate it using approved math and keep records.

- All gas burnt or released must be reported to Petrinex.

Flaring & Venting Records

Companies have to keep a "flare and vent diary" for a year. They have to explain what happened and how long each event lasted. They must also disclose how much gas was released and how they did the math. It's also in the log if someone complains - including how the company handled it.

Appendix A - Special Venting Rules

PRODUCTION TANKS WITHOUT CONTROLS

Unless they're hooked up to a capture system, production tanks can burp out natural gas. Burps can be big, so the rules limit them:

- Newer facilities have to keep venting below 1250 m3/month.

- For the time being, older ones get a higher limit, 9000 m3/month.

- New and modified facilities won't be allowed to vent from tanks.

- Tank venting must be reported to the regulator every month.

PNEUMATIC DEVICES

Like little robot helpers, these gadgets run on gas pressure. There are some who constantly release gas; there are others who only puff occasionally. Here's what the rules are:

- New sites and big compressor stations can't use venting devices.

- Older sites can only use them if they vent very little. Modified facilities must replace venting devices with non-venting ones soon.

- Whenever possible, companies should switch to electric or air-powered devices.

PNEUMATIC PUMPS

Gas pressure is also used to push chemicals into pipelines. Also, newer and modified sites can't vent from these pumps. Older sites can still use them, but only for 750 hours a year.

METHANE LIMITS FOR FLEETS

Every company gets a methane "budget" for all its pneumatic devices and pumps. The budget depends on how many active wells and facilities they had in 2021.

RECIPROCATING COMPRESSOR SEALS

As the seals wear out, they leak more gas. Here are the rules:

- If they run long hours, big compressors installed after 2021 can't vent seal gas at all.

- The whole fleet has to stay below an average leak rate.

- There's no way a compressor can go over the worst-case scenario.

- Newer or modified facilities won't be allowed to vent.

CENTRIFUGAL COMPRESSOR SEALS

Instead of pumping back and forth, these compressors spin. They can leak too:

- Older compressors have higher venting limits, newer ones have stricter ones.

- Future sites and modified sites can't vent seal gas, like other equipment.

- Each compressor counts separately even if they share a driver.

An Approval is Just What you Need

Feeling the pressure of a looming deadline? We get it. You need dependable, and regulator-respected solutions when you're operating in BC's dynamic energy sector. You can't afford to delay your project's approval any further - or your company's environmental reputation.

A model isn't enough; you need confidence. We turn air quality dispersion modelling into a streamlined approval process.

Our dispersion modelling team is one of the most experienced in Canada. In addition to meeting the standards, we have trained regulatory personnel who set them.

You have a situation that needs a solution. Our goal is to deliver.

We use industry-leading models like AERMET or CALMET to process the right five-year, site-specific meteorological file with your operational data. Incorporating surrounding terrain info and emissions from nearby sources is a meticulous process. The control files we prepare for AERMOD or CALPUFF ensure your BC flare stack and other source modelling strictly adheres to all provincial and national regulations.

Both preservation of the environment and economic viability depend on this work. Not only do we provide a full report with graphics that can be submitted immediately to the authority, we analyze the modelling results and compare them against air quality standards and human health metrics when needed.

Don't agonize over compliance. Get approved now. Whether routine or emergency, we can prove that your operations are managed with world-class safety and environmental practices.

We can help you solve this problem today. Are you ready to move forward? Get in touch with Barry at this address...

...immediately to discuss your needs regarding dispersion modeling assessments. Feel free to contact us if you need assistance.

Clean air is our Passion...Regulatory Compliance is our Business.

In today's evolving energy landscape, flare rules, emissions management, personality science, and real-world project challenges all connect.

I try to give young thinkers a quick, entertaining rundown on what matters, why it matters, and how to take the next step in building a meaningful career.

Do you have concerns about air pollution in your area??

Perhaps modelling air pollution will provide the answers to your question.

That is what I do on a full-time basis. Find out if it is necessary for your project.

Have your Say...

on the StuffintheAir facebook page

Other topics listed in these guides:

The Stuff-in-the-Air Site Map

And,

Thank you to my research and writing assistants, ChatGPT and WordTune, as well as Wombo and others for the images.

OpenAI's large-scale language generation model (and others provided by Google and Meta), helped generate this text. As soon as draft language is generated, the author reviews, edits, and revises it to their own liking and is responsible for the content.

New! Comments

Do you like what you see here? Please let us know in the box below.